Written by Judy Penz Sheluk

-Published: Antiques Journal, May 2012.

In our regular column, Hammered Down, we talk to auctioneers. This month, for a change, we talk to a dealer.

Austin T. Miller shows us the backstage work of an antiques dealer.

“I purchased this sign without any provenance from another dealer at the New Hampshire Antique Antiques Show,” Miller said. “I hired a professional researcher, Madelia Ring, to go to the town of Tamworth, N.H., and see what she could find. Provenance is so important, and in this case, it made this trade sign infinitely more interesting and salable; it becomes an entirely different object – you just don’t get trade signs with this much information.”

Miller admitted that sometimes a researcher will spend 80 to 100 hours on an object and come up empty. “I always cap the amount of research, as it can run into several thousand dollars, so naturally, when nothing can be found, it’s disappointing. But in this case, Madelia found out a lot of information, which will of course now stay with the sign.”

What the research revealed: The artist who painted this sign, Caleb William Heath, was born Aug. 19, 1835 in North Conway, N.H., the son of George W. Heath (died 1836) and Maria. Lang (1804-1888). On Dec. 9, 1857 George William Heath was married to Olive Ann Clark (born Feb. 28, 1837 in Bangor, Penobscot, Maine) in Lawrence, Mass., where the couple resided, with his occupation cited as a painter. In the 1860 census for Lawrence, Mass., his occupation is cited as a painter. In 1862, when he was enlisted to serve in the Civil War, his occupation is cited as painter. In the 1870 census, he is cited as a resident of Boston with an occupation of housepainter. At the time of his death in Lawrence, Mass. on Sept. 19, 1875, his occupation was once again cited as that of a painter.

Given that Caleb Heath was recorded as a resident of Lawrence, Mass. at the time of his marriage in 1857 and when he enlisted as a soldier in the Civil War in 1862, and in 1870 he was residing in Boston, it seems relatively certain that he painted the sign prior to the Civil War.

Pictorial blacksmith trade sign for John Chick, Caleb William Heath (1835-1875), Tamworth, N.H., c. 1857. Oil paint on softwood panel, 24 x 32 in., original brass ring hangers. Signed side A: “C.W. HEATH LAWRENCE MASS.” Signed side B: “W. HEATH painter LAWRENCE MASS.” Price on request.

Because the sign lacks any reference to the name of the business or a blacksmith, it is highly improbable that it would have been commissioned for a blacksmith’s premises in Lawrence, Mass., where more than 10 blacksmiths were aggressively competing for patronage during this period. Instead, the attributes of this sign suggest it was designed to be displayed in a more rural setting where imagery on signs had to be easily understood by those passing by, literate or otherwise. It is interesting to note that Caleb Heath, a New Hampshire native, has included a distant view of the familiar White Mountains into the background of his sign.

Investigation into the family of Caleb’s wife has established that the sign was undoubtedly made for a blacksmith working in Tamworth, N.H. rather than one in Lawrence, Mass. It appears that Caleb’s father-in-law, John Clark (1794-1873), probably made the arrangements for his young son-in-law to make this sign for the village blacksmith at this time, John Chick. These two families were close and related through marriage. John Clark’s eldest son, William, born in 1824, was married to Chick’s youngest daughter Ruth. As John was a carpenter by trade, it seems possible that either John or his son Albion, born in 1827 and also a carpenter, constructed the sign and then arranged for Caleb to paint it.

The Tamworth, N.H. blacksmith John Chick was born in 1799 in Limington, Maine, the same place of birth as the mother of Caleb Heath. He married Lucy Ann Bryant on Sept. 9, 1822. She was born in Tamworth, N.H. and died there on April 16, 1846 at the age of 46 years. John Chick’s name appears in census records for Tamworth, N.H. from 1830 to 1850. He died on Sept. 11, 1858.

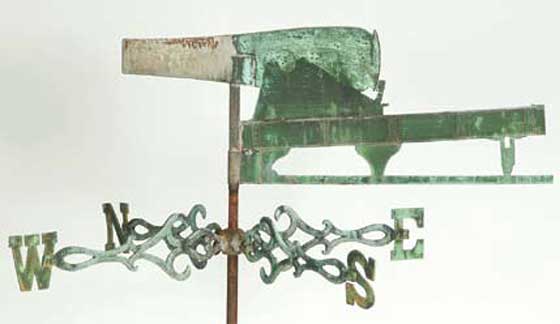

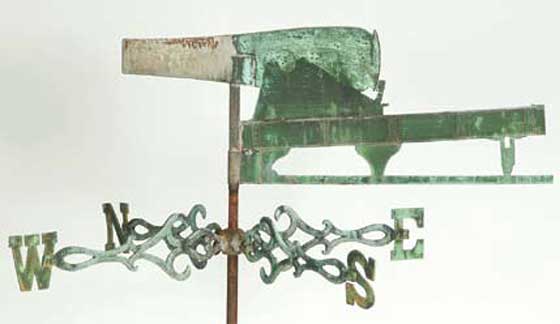

Molded and sheet copper cannon weathervane and directionals, made by J. Howard & Co., Bridgeport, Mass., copper with original verdigris and cast-zinc barrel cannon: 18 in. x 39 in. x 5 in.; base: 76 in. x 47 in. x 47 in., $30,000.

The eldest son of John and Lucy Ann Chick, Walter (1822-1888) does not appear to have carried on the trade of blacksmithing, as he is cited as a farm laborer for John T. D. Folsom in Tamworth in the 1860 census. Their daughter, Hannah, born in 1836, married her first cousin, Wyatt Bryant and they had five children which they raised in Tamworth. The home in which this sign was discovered is located at the fork of the road immediately adjacent to the original Bryant farmhouse at #249 Bryant Road in Tamworth, N.H. which was built about 1820. Within Tamworth circles, the house is commonly referred to as Wyatt’s house, referring to Wyatt Bryant, the son of John Bryant and Mary Chick, the sister of the blacksmith John Chick. In 1853, Wyatt married his first cousin, Hannah Bryant Chick (born 1833). She was the daughter of the blacksmith John Chick and Lucy Ann Bryant, and the sister of Ruth Chick, sister in law of Caleb Heath who painted the sign. In the latter half of the twentieth century, this house was occupied by Wyatt’s great-granddaughter Marion Edith Smith. Following the death of Marion Edith Smith, her property passed to her friend Margaret R. Jackson, who resided in the Bryant homestead until her death in July 2008. The entire contents of this household were then sold at public auction in September 2008. Included in the sale was the sign from the blacksmith shop of John Chick. Owing to the fact that it was only used by John Chick for perhaps one year and then having been sequestered in this house from the time of John Chicks death in 1858 until 2008, the sign has survived in a remarkable state of preservation.

“Cannon-form weathervanes, though most popular immediately preceding the Civil War, are rare survivors and this vane, with its original directionals, is an exceptional example,” Miller said. “Further elevating this vane above other cannon-form examples is the clean lines of the silhouette. The use of zinc for the barrel and directionals was typical of the weathervanes made by Jonathan Howard and Company of Bridgeport, Mass. The weathervanes manufactured by the Jonathan Howard Company from 1852 to 1857 are regarded as the most aesthetically pleasing, desirable and stylized weathervanes ever produced, rivaled only by those of the A.L. Jewell Company of Waltham, Mass.”

This weathervane was previously situated atop the Arsenal Officer’s Club Building in Watertown, Mass. The arsenal was established in 1816, on 40 acres of land, by the United States Army for the receipt, storage and issuance of ordnance. In this role, it replaced the earlier Charlestown arsenal. The arsenal’s earliest plan incorporated 12 buildings aligned along a north-south axis overlooking the river. Buildings included a military store and arsenal, as well as shops and housing for officers and men. All were made of brick with slate roofs in the Federal style; a high wall enclosed the compound. By 1819 all buildings were completed and occupied.

The arsenal’s site, duties and buildings grew gradually until the American Civil War, when it grew beyond the original quadrangle. During the war it greatly expanded to produce field and coastal gun carriages, and the impetus of the war led to the quick construction of a large machine shop and smithy shop built as contemporary factories, as well as a number of smaller buildings.

The arsenal is located on the northern shore of the Charles River in Watertown, Mass. and is now registered on the list of historic civil engineering landmarks as well as the National Register of Historic Places.

Elijah Pierce was born the youngest son of a former slave on a Mississippi farm on March 5, 1892. He began carving at an early age when his father gave him his first pocketknife. By age 7, Elijah Pierce began carving little wooden farm animals. In his teens, Pierce decided he didn’t want to be a farmer.

Elijah Pierce (1892-1984), Two Farmers Talking, Columbus, Ohio, dated Feb. 23, 1973, carved and polychrome painted wood with glitter. Artist framed 13 x 13 in. $24,000.

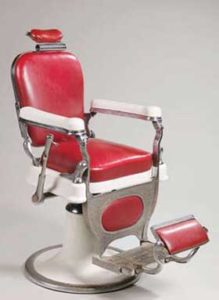

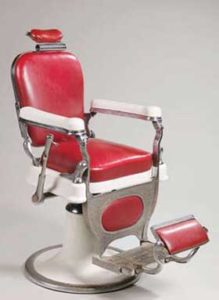

Theo A. Kochs Company, Elijah Pierce barber chair, 1930s-1940s, metal, enamel and leather. Photo courtesy Garth’s Auctions, Delaware, Ohio.

However, he had taken an interest in barbering. Pierce began hanging out at a local barbershop in Baldwyn, Miss. and it was there that he learned his trade. He migrated north to Columbus in 1923. In 1951, Pierce became self-employed with the opening his own barbershop at 483 E. Long St. in Columbus, Ohio. After his death, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Performing and Cultural Arts Complex recognized his work by naming the Elijah Pierce Gallery in his honor. The Columbus Museum of Art now owns the vast majority of Pierce’s carvings – over 300 pieces. “In excellent original condition, this fine early plaque, purchased directly from the artist, was in the same private collection for about 37 years,” Miller said. “About three years ago, Elijah Pierce’s barber chair and his original barber sign came for sale at Garth’s Auction in Columbus, Ohio. I try to be a supporter of Folk Art, so I purchased it for the Columbus Museum of Art, where it is now on exhibit.”

Painted dressing table, New York state or New England c. 1816, popular and chestnut, H 28 in., W 28 in., D 28 in. $55,000.

“The original painted decoration on this dressing table emulates decorated tinware,” Miller said. “It is a very sophisticated piece of painted furniture, with a refinement and delicacy typical of New York state or New England, and everything about it is absolutely wonderful, from the provenance of a famous collection, to the near pristine condition. This would have been used in a bedroom. The small box on top is referred to as a glove box, although of course, people would store many things inside it. Inscribed inside of the long drawer is ‘May 16, 1816.’”

Provenance: Collection of the John Tarrant Kenny Hitchcock Museum, Riverton, Conn.

About Austin T. Miller: Austin T. Miller American Antiques Inc. was started by Richard and Shirley Miller in Columbus, Ohio, and was originally incorporated as American Antiques Inc. in 1976. They were regarded as two of the finest and most reputable American Antique dealers in the country. Their son, Austin T. Miller adheres to the same uncompromising standards.

About Austin T. Miller American Antiques, Inc.: A dealer in Americana specializing in American folk art and country and formal American furniture and accessories, commonly sought items from within the American Folk Art Collection are weathervanes, whirligigs, folk art paintings and paint decorated folk art.